(Image credit: Future)

This month I’ve been testing: Not very much, actually! Well, a spot of cable-hiding tech by Asus and one of Gigabyte’s latest laptops, but I’ve mostly been testing out a new display panel colorimeter. It’s surprising how much your eyes deceive you when looking at a monitor.

PCI Express has been the standard system by which to send data and instructions around a computer for two decades. The specification for how it all works has gone through regular updates, each one offering double the performance of its predecessor. PCIe 5.0 was released almost four years ago and it’s the most recent version you’ll find in any gaming PC right now. It’s also virtually worthless, thanks to the disappointing hardware that supports it.

For a computer to support PCIe 5.0, it needs one of two things, though preferably both. First up is the CPU—all of the latest generation of processors from AMD and Intel have PCIe 5.0 controllers built into them. Ryzen 7000-series chips have 28 lanes of Gen 5 PCIe that are split so that the first 16 are allocated to the graphics card slot, eight are dedicated to M.2 NVMe slots, and the remaining four are used to communicate with the motherboard chipset (more on that obfuscating mess in a moment).

Intel’s 14th Gen Core processors have the same number of lanes as AMD, but it’s all split quite differently. Only sixteen of them are PCIe 5.0 and the rest are the slower 4.0 spec; however, eight lanes are used for the motherboard chipset, leaving scope for a single SSD to be connected directly to the CPU. Well, not quite, as the 16 Gen 5 lanes can be switched into an 8+8 mode, half for the graphics card and half for SSDs (AMD’s chips can also do this).

Still, on paper, AMD has Intel thoroughly beat when it comes to PCIe 5.0 support. However, things become more complicated with Ryzen processors because to access the full range of Gen 5 lanes, you need a motherboard that uses E-versions of the latest chipsets. For example, an X670 board will have a PCIe 4.0 graphics card slot and no more than a single PCIe 5.0 SSD slot. Switch to an X670E motherboard and the GPU slot will be 5.0 and there could be two Gen 5 M.2 slots (though it’s usually just the one).

AMD’s chips have lots of PCIe 5 lanes on offer but using them all is another matter. (Image credit: Future)

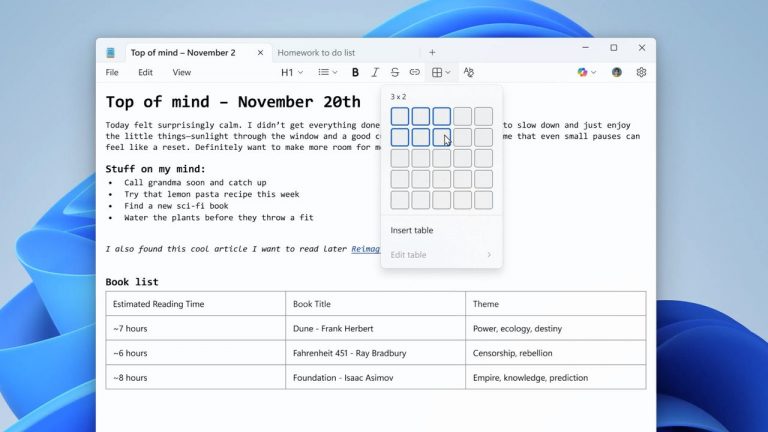

If that’s a tad confusing, then I can assure you, it’s a better state of affairs than Intel’s current PCIe 5.0 support. Take the ASRock Z790 Nova motherboard, as an example. It’s a lovely board, well built, and has a total of six M.2 SSDs. Two of these are directly wired to the CPU, for the best performance, and the one closest to the processor supports a PCIe 5.0 SSD. Unfortunately, if you put any SSD into that slot, the CPU automatically switches the graphics card slot to eight lanes (aka PCIe x8).

While that still leaves the other eight Gen 5 lanes available, they can’t be split any further and since M.2 slots always use four lanes, you’re wasting four PCIe 5.0 lanes by using that first SSD slot. Even if you use a Gen 4 or even Gen 3 SSD. Not all Intel motherboards do this but those that use the Z790 chipset and sport a Gen 5 SSD slot will have this limitation.

But it’s not just the SSD slots that Intel makes a mess of. A single PCIe 5.0 lane has a bandwidth of just under 4 GB/s, so eight of them aggregate to a total of 31.5 GB/s (let’s just call it 32). That’s the same as 16 lanes of Gen 4 so, in theory, putting a Gen 5 graphics card into an eight-lane slot shouldn’t be a problem.

Except there aren’t any Gen 5 graphics cards—they’re all still using PCIe 4.0, at best. The next round of new GPUs from AMD, Intel, and Nvidia may move to the newer spec but given that they’ve only just changed to Gen 4 in their latest generation of cards, there’s a good chance that they won’t.

Use that ‘Gen 5’ SSD slot and kiss goodbye to half your GPU slot lanes. (Image credit: ASRock/Intel Corporation)

So, if you’re like me, and have that ASRock Z790 motherboard, no matter what GPU you use, if you stick an SSD into the first M.2 slot, then the card will be forced to run in PCIe 4.0 x8 mode (the same as Gen 3 x16). Fortunately, no game comes anywhere near maxing out the bandwidth of the PCI Express graphics card connection but who’s to say that this won’t happen soon?

All of these frustrations would be forgivable if PCIe 5.0 SSDs were brilliant and worth buying. The sad fact of the matter is that they’re a waste of money. Sure, the peak performance in synthetic tests makes older Gen 4 drives look positively slow in comparison, but in real use, you’ll barely notice the difference.

That might seem very odd, given that one of the few PCIe 5.0 SSDs worth considering has peak sequential read/writes well over 10,000 MB/s—a basic Gen 4 drive will only be half that rate. The reason is that games, applications, and even entire operating systems have all been designed around moving small amounts of data and only when needed, because most PCs don’t have very fast storage. Gen 5 SSDs can only show their true limits in very specific scenarios, few of which are ever experienced in gaming or general PC use.

Then you have price and heat rubbing salt into the wound. Head over to the likes of Newegg and look at how much a genuine Gen 5 SSD costs, i.e. ones that make full use of the connection’s performance. You’re looking at $150 or more for a 1TB PCIe 5.0 SSD and for that amount of money, you can get one of the best 2TB Gen 4 drives and still have change.

Is Gen 5 really suffering from early adopter problems or is it a case that vendors aren’t interested in supporting it all properly?

All Gen 5 SSDs run hotter than Gen 4 ones and it’s not by a few degrees. You have to use a decent cooling system, be it a dedicated heatsink and fan, or a large metal heatsink on the motherboard to absorb and dissipate the heat. In the case of the former, that’s an additional cost to consider and depending on the size of your graphics card, you might not have room for it.

One could argue that this is just a case of ‘early adopter’ problems and that it will all get much better as the technology advances. While that’s certainly true, it’s worth noting that the PCIe 5.0 spec was released almost four years ago, and AMD’s Ryzen 7000-series came to market in the second half of 2022. So is Gen 5 really suffering from early adopter problems or is it a case that vendors aren’t interested in supporting it all properly?

It’s a bit of both, to be honest. Each successive revision of PCI Express doubles the amount of bandwidth each lane has and up to version 5.0, this has been achieved by running the bus clocks twice as fast. Try doubling your CPU or GPU clocks and see what happens. Okay, it’s not the same thing, but massively ramping up clock speeds isn’t an easy task, even with a relatively simple system like PCI Express. Electrical tolerances need to be extremely tight, which adds to the complexity and cost of everything.

This is especially true for SSDs. To be fully PCIe 5.0 compliant, the controller chip needs to run faster than a Gen 4 one and the NAND flash memory chips also need to read and write data at a much higher rate. At the moment, very few companies have chips that can do all of this and those that can, unfortunately, generate a lot of heat. The market for Gen 5 SSDs is much smaller than that for Gen 4 drives, so the tiny demand means the relative costs are higher, too.

Gen 5 SSDs—fast, hot, and expensive. Umm, no thanks. (Image credit: Future)

That all said, AMD and Intel haven’t done the best of jobs when it comes to actually implementing PCIe 5.0—in the case of the former, the Gen 5 graphics card slot is wasted, as nobody sells a Gen 5 card, and the deliberate chipset limitation between E and non-E motherboards just adds confusion to it all. It’s also completely unnecessary, as there’s physically no difference between the chips used in, say, a B650 and B650E motherboard.

Intel clearly wasn’t all that interested in Gen 5 PCIe, as its implementation in its 14th Gen desktop CPUs and 700-series chipset amounts to a PCIe 5.0 x16 slot, a maximum of one Gen 5 M.2 slot, and a whole bunch of irritating configuration restrictions. It doesn’t look like Intel will be offering anything significantly better with Arrow Lake, either.

PCIe 5.0 is pretty much useless at the moment or at the very least, used-less, if that makes any sense. Support for it in the immediate future doesn’t look that much better, either, but fortunately for us, Gen 4 is more than good enough. That technology is coming up to being seven years old now but we’re still way off the point where it’s a limitation in gaming. At some point in time, every desktop PC will be fully Gen 5, from top to bottom, though at the rate that PCI Express gets implemented, we won’t need to worry about that for a long time.

Let’s hope that we’re not having the same problems again but with Gen 7 or the like!