Even with its shortcomings at launch, I was always strongly affected by Cyberpunk 2077’s portrayal of living on borrowed time. The denial, the bargaining, the pills you’re prescribed that barely seem to do anything: it’s all cut from a very real cloth, one I know well after a half year of preparing for something only marginally better than my central nervous system getting slow-cooked by a neuro-degenerative terrorist. Thankfully, my prognosis looks less grim now, but I’ll never forget experiencing the two side by side.

Indeed, Cyberpunk 2077 “is about terminal illness, and it’s about coping with that” according to Paweł Sasko, quest lead on 2077 and associate director on CD Projekt Red’s upcoming Cyberpunk game. “How am I going to spend these last six months? Am I going to become a legend and drown in luxurious cars and all of those material things, or am I going to spend it in a relationship, and really be with people?'” (Spoilers for the base game and Phantom Liberty expansion ahead!)

“The game’s starting out and a lot of people thought or felt, ‘Yeah, it’s going to be GTA.’ And then there was this creeping thing that was always there, slowly actually taking over and making you realize,” Sasko told fellow Night City devotee Ted Litchfield in an interview back at the Game Developers Conference. “Some players didn’t get it, but some players did, actually, and those that did, it touched them really deeply.”

My Baldur’s Gate adventuring party of medical specialists make the Office Jim face when they look at my charts.

I was definitely one of those people touched. Concurrent to Cyberpunk 2077’s unprecedented resurrection last year from the ashes of its apocalyptically bad launch, I was undergoing the screening process for ALS, a rapid, degenerative condition that robs people of their motor control, their speech and their autonomy. Life expectancy after onset is short, and some opt for some form of medical euthanasia once the disease progresses far enough. You may faintly recall that, on an earlier, more credulous internet, a lot of people took an “ice bucket challenge” to call attention to themselves as good people (or people who shouldn’t be allowed to borrow tractors).

Having lived to the ripe old age of 26, I’m now at a point where the degenerative effects of cerebral palsy have started to set in fast and hard enough to have my Baldur’s Gate adventuring party of medical specialists making the Office Jim face when they look at my charts. That grim hemming and hawing was one of the first obvious parallels I noticed between my brush with terminal illness and V’s: the way Vic refuses to look at you before being all like “I’m gonna level with ya, kid,” or Misty’s clasped hands solemnity as she eases you into what’s coming.

“Cyberpunk is about you, as a player, discovering this disaster for yourself. And there’s so many people that I think their discovery was: ‘I just want more cars. I’ll just drown in material goods. And that’s it, and that’s the way I live my life,'” Sasko continued. “When players were like, ‘Holy hell what choices am I making? If I cannot really save myself, what kind of RPG is this?’ It’s about finding the answer. What is your answer to terminal illness?”

It’s a heavy question, and even drawing on my personal experience, one that I can’t really answer. I remember getting the call from my doctor telling me that I was being referred to a neurologist for a nerve conduction study and thinking, “Wow, if I do have ALS, I really need to finish my Warhammer army before it progresses too far.” It’s a thought emblematic of a type of denial, sure, but the experience gave me a strange new perspective on quests in open world RPGs of all things.

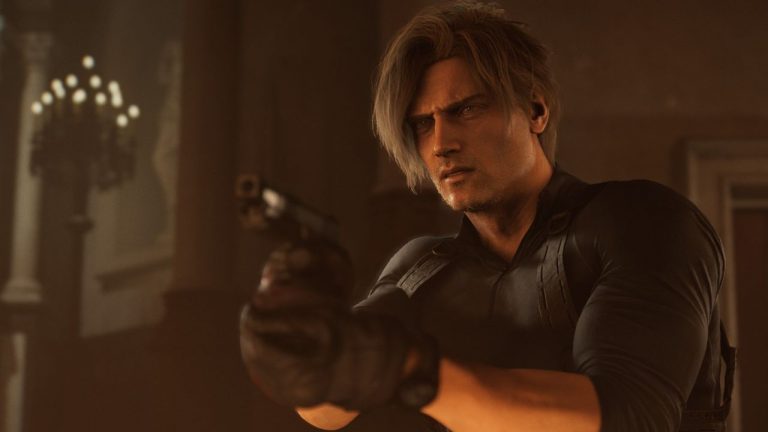

(Image credit: CD Projekt)

So often we bemoan this on again/off again mode of urgency in the genre, where matters of life and death fall by the wayside in the face of side quests that feel like they should barely matter in the grand scheme of things: clearing out bases of Scavengers and selling their body parts without a second thought, becoming a street racer but only during the daytime, and pretending to be a first responder so you can afford a new car are some 2077 offenders.

But honestly, that’s a much more accurate portrayal of what living through something like this is like. You just gotta do you regardless—for me, that was playing Cyberpunk 2077, working on Chaos Space Marines, and learning to DJ. Maybe fucking around for five hours before nuking Megaton for no good reason when you’re supposed to be looking for your dad is the most realistic thing in Fallout 3.

Panacea

“There is a way to survive,” Sasko noted, referring to The Tower, a new base game ending added in Cyberpunk 2077’s expansion, Phantom Liberty. “But the way you pay: you’re in coma for two years, you wake up, everything’s different. You pay the ultimate price with the relationships with all of those people.

“You just lost almost everything. But you survived and that was the thing we wanted to give them. In a way, it’s a bit more hopeful, but the price is really high.”

Playing through Phantom Liberty pre-launch for PC Gamer coverage, before anyone really knew what was in store, was a really personal experience—once I had the promise of a cure dangled in front of my V, I opted to drop any and all pretenses of role playing aside from securing it. The stakes were simply too high: Phantom Liberty presented a once in a lifetime gaming experience, my avatar offered the kind of moonshot miracle I could never find in real life.

The entropic force I was preparing to stare down had no remedy, no cure, promising to rob more of me each day. Circumstances had transpired in such a way that “How far would you go for a chance at a cure?” proved to be one of the most engrossing, thought provoking, and immersive questions I had ever been asked in an RPG.

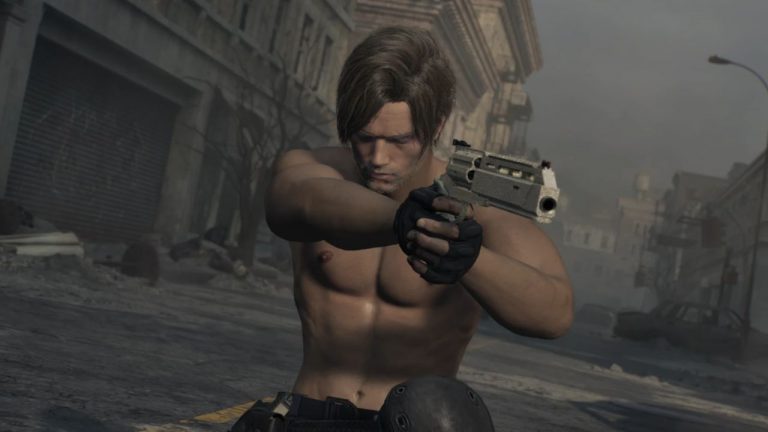

(Image credit: CD Projekt Red)

Entertaining the thought of a life like V’s haunts me more than any diagnosis.

And Sasko was right, it’s a brutally high price, so high that when I reflect on Cyberpunk 2077 now, Phantom Liberty and The Tower are almost all I can think about. Songbird’s betrayal of my trust—her own offer of a cure revealed to be a ruse—felt deeply personal, and I was legitimately angry. It felt like it was me standing there on that spaceport deck, not V, and I was left to decide whether Songbird would head for the moon to get the lifesaving care she needed, or stay on terra firma to face a life of degradation as an NUSA guinea pig in exchange for the government’s potentially lifesaving expertise for myself.

I don’t know how I would handle this choice in real life, were it presented to me. Without directly encountering a moment like that, I don’t think anyone can honestly know how they might react, how far they would go, or if they would even want to continue living. What I can tell you is that I turned Songbird in, got the surgery, and saw my V wake into a despair ridden life so similar to my own: They survive, but are vastly diminished, unable to use the setting’s ubiquitous cyberware that facilitates everything from high-stakes mercenary work to everyday bank transactions.

V speaking with Reed and their medical team after waking from the coma was uncomfortably reminiscent of discussions I continue to have with my own doctors, each one imparting a similar message: that I should steel myself for what’s to come, to reign in my expectations for how far I can go, and be ready to compromise on my ambitions, passions, and dreams.

(Image credit: CD Projekt Red)

However, what was most affecting about The Tower was that the life that V walked back into was totally devoid of the light that my fiance, my friends, my family, and my colleagues were providing me in a time where I could see nothing but darkness ahead—in the intervening two years, all of V’s friends, associates, and potential lovers move on with their lives and leave them behind. It’s not malicious, and that almost makes it worse.

Entertaining the thought of a life like V’s haunts me more than any diagnosis. My own flirtations with medical euthanasia were cut mercifully short as I was screened out of an ALS diagnosis through the arduous, nerve wracking process of exclusion a few months back. I’m still wracked with alien neurological torments, but the worst of all worlds, thankfully, is not to be—I think.

I have returned to Cyberpunk 2077 a handful of times since, as Phantom Liberty’s astounding quality and the psychic siege-like conditions that I played it under have cemented it as an all-time favorite. Ultimately, what keeps me from ever getting too far into another playthrough is a feeling that I’ve committed to an ending already—for V, and for myself.